Rivers in Art

I was in Washington DC this week at meetings with my colleagues with the Hydropower Reform Coalition who work to represent the public interest in the regulation of hydropower facilities for the benefit of fish, wildlife, people on our nation's rivers. It was a good week as I met with a couple of the new Commissioners over at the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission and also had a chance to sit down with Senator Murray. While the policy work was fun, it was a real pleasure to have a bit of time between meetings to view some of my favorite paintings on display in the museums. I have always been a real fan of 19th century American Painting, and in particular the Hudson River School, since my art history classes in high school and our trips to view Thomas Cole's Voyage of Life on display at Munson-Williams-Proctor Institute in Utica, NY just a short drive from the town where I grew up.

The art of this period parallels the exploration and settlement of the American Frontier and explores the wilderness landscape in a sharp departure from European art of the same period. At the same time that the artists of the Hudson River School were interpreting the rivers, forests, and mountains of the nation poets such as William Cullen Bryant and writers such as Henry David Thoraeu and John Muir were beginning to explore themes that would form the foundation for an American concept of Wilderness, a concept that was later refined by individuals such as Aldo Leopold and Bob Marshall and ultimately tackled by Congress with the passage of the Wilderness Act.

I found this painting of Niagara Falls painted by Alvan Fisher in 1820 tucked away in a hallway in the Smithsonian Museum of American Art. It's an interesting painting representing one of the early illustrations of a scene that was soon to become a symbol of the epic scale of America's scenic wonders and natural beauty.

In a departure from the more traditional views looking upstream at the falls that were painted by Fisher and others, Frederic Church took a dramatic approach by placing the vantage point right at the lip of Horseshoe Falls on the Canadian side in his 1857 painting of Niagara Falls. Unfortunately this painting, owned by the Corcorran gallery, was off on tour so I did not actually get to see it in person. I love this painting because it is my favorite depiction of the power of water and really draws you in with the energy you experience at the lip of a big waterfall.

The Jolly Flatboatmen was painted in 1846 and hangs over in the National Gallery and has always been one of my favorite paintings. The thing I really enjoy about this painting is the connection between people and the river. Our transportation system is dominated by highways, trains, and air transport but at one time rivers were the primary highway of commerce.

I have always had this focus on American landscape paintings and have not spent much time exploring what the European artists were up to at the time, but while I was in town the National Gallery had a great show of John Contstable's paintings of the Stour River in England. These are the 6 foot landscapes and the White Horse which was in the show and seen above was painted in 1819. What's interesting about these paintings is the contrast with the American experience that we see in the paintings of the Hudson River School that were to come a few years later. The Stour River is depicted as a working river with tow paths, locks, mills, and dams. The show was fascinating because it paired up the finished landscape paintings with full size oil sketches and smaller drawings that Constable made in develop the concept for a painting. Now spread throughout museums around the world the paintings and studies were all brought together in one show.

Turning back to the American experience and an appreciation for the scenic wonders of the continent, one is drawn to the paintings of Thomas Moran. Moran is well known for his spectacular images of Yellowstone. His watercolors along with the photographs of William Henry Jackson played a pivotal role in the creation of America's first National Park. As no members of Congress had been to Yellowstone, Ferdinand Hayden, who led the 1871 government survey to Yellowstone, brought the visual testimony to Capitol Hill. The approach proved effective and the Park was established in 1872. Shortly thereafter Congress appropriated $10,000 for the purchase of Moran's painting, The Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone. The river remains the longest undammed river in the Western United States at 671 miles from its source to the Missouri River.

The painting now hangs in the Renwick Museum just a couple blocks from the Whitehouse along with two other large Moran landscapes and framed by dozens of George Catlin paintings of Native Americans on the great plains. It's a neat gallery set up in the style of a 19th century museum.

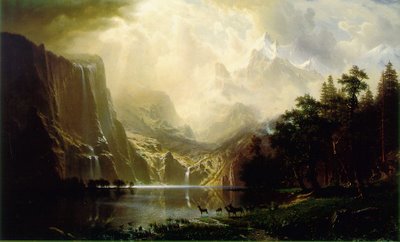

Albert Bierdstadt painted some of the most famous images of the Sierras from the 19th century as he provided a visual representation of a landscape that John Muir was writing about.

Bierstadt's painting is wonderfully displayed in an alcove in the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

As the 19th century passed into the 20th century we would see more art that would explore themes of taming the wilderness frontier. While it does not depict a river, I have always enjoyed Lackawanna Valley painted by George Inness in 1855 and on view in the National Gallery. It is one of the early paintings to introduce industrial progress into the American landscape. A train transports coal through the valley and the fresh-cut tree stumps show a landscape that has been recently cleared.

Thomas Hart Benton s 1947 mural Achelous and Hercules, in the National Museum of American Art, portrays the taming of the land and its bounty, and specifically the Missouri River that the Army Corps of Engineers was busy harnessing for the "benefit" of society. In Greek mythology Achelous is the diety of rivers and although he would assume different forms he is typically depicted as a bull. Hercules broke off one of his horns and it became the Cornucopia. The Army Corps of Engineers was working to harness the "wild river" that tore off like a bull across the floodplain each spring. Only now are we beginning to consider the ecosystem services naturally flowing rivers provide, and the expense incurred in trying to control them (see John McPhee's The Control of Nature).

So that was the trip to DC. I could write about all our meetings that consumed the bulk of my time but it's not often I get a chance to see these great paintings.