Restoration of the Elwha River

Originally Published in the Mountaineers Magazine, July/August 2013

The Elwha River is unique among rivers of the Olympic Peninsula with a watershed that represents approximately 20% of Olympic National Park and headwaters reaching to the very center of Olympic Mountains. These mountains were formed by the domal uplift of marine sedimentary rock and basalt that the powerful Elwha River has carved its way through. The rich geologic diversity that resulted has been sculpted by the action of flowing water, the errosive power of sediment, and the persistent grinding action of the glaciers that have all shaped the landscape. The Elwha River of recent geologic history has all the attributes of river that is well suited for the suite of species that comprise the Pacific salmon, its deep canyons and diverse geology create one of the region’s classic backcountry whitewater destinations, and all the power and volume of a river descending from the mountains to the ocean over a distance of just 40 miles made the river an early candidate for hydropower development.

The Elwha River is unique among rivers of the Olympic Peninsula with a watershed that represents approximately 20% of Olympic National Park and headwaters reaching to the very center of Olympic Mountains. These mountains were formed by the domal uplift of marine sedimentary rock and basalt that the powerful Elwha River has carved its way through. The rich geologic diversity that resulted has been sculpted by the action of flowing water, the errosive power of sediment, and the persistent grinding action of the glaciers that have all shaped the landscape. The Elwha River of recent geologic history has all the attributes of river that is well suited for the suite of species that comprise the Pacific salmon, its deep canyons and diverse geology create one of the region’s classic backcountry whitewater destinations, and all the power and volume of a river descending from the mountains to the ocean over a distance of just 40 miles made the river an early candidate for hydropower development.

The Elwha Dam was not the first dam across the Elwha as the Vashon ice sheet dammed the river forming glacial lake Elwha a little over 10,000 years ago. Beneath the forest canopy the observant hiker can find evidence of glacial terraces, perched deltas, and moraines that provide evidence of the old lake that disappeared with the retreat of the glaciers. As can be observed today in Alaska where glacial retreat has exposed new river habitat, salmon discovered the Elwha and found a rich diversity of habitat. The powerful rapids and cascades of canyon sections of the Elwha exerted strong selection pressure for massive Chinook salmon, pink salmon found ideal habitat in the lower gradient reaches closer to the ocean, and sockeye had access to important rearing habitat in Lake Sutherland. The abundant fishery resource became an important food and cultural resource for the Klallam people, central to the identify of those who called the valley home.

In 1882 the world’s first hydroelectric

project began operation on the Fox River in Wisconsin and with it came ambitous

plans to harness the power of rivers to generate electricity and fuel

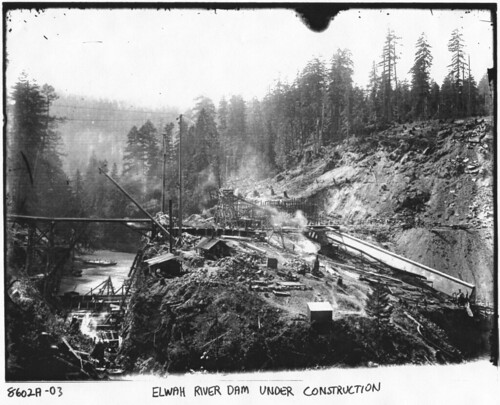

industrial development. Thomas Aldwell located a homestead on the Elwha and

slowly began accumulating the land necessary for the development of a hydropower

project over a period of 20 years. Where the Klallam people had found a fishery

resource that sustained their community, Thomas Aldwell looked upon the river

and determined that it was “no longer a wild stream crashing down to the

Strait; the Elwha was peace and power and civilazation.” As Aldwell worked to

secure the financing, construction of the Elwha dam commenced in 1910. The dam

was not anchored to bedrock but instead set on glacial alluvium—“a dam on

roller skates.” Shortly after construction in October of 1912, the dam failed

in spectacular fashion when the river blew out through the gravel below the

dam. Rebuilding commenced and by the end of 1913 the Elwha was no longer a

free-flowing river as electricity flowed from the powerhouse to Port Angeles

and beyond.

Decommissioning the hydropower projects on

the Elwha was a project that took several decades. By 1927 a second dam had

been constructed at Glines Canyon which was subsequently included within the

boundaries of Olympic National Park. In the mid 1980s as the Federal Energy

Regulatory Commission (FERC) continued to slow walk the license applications

for the two dams, Rick Rutz made the observation that FERC did not have the

jurisdictional authority to license a hydropower dam in a National Park. It

took several years but by 1992 the audacious idea to remove the dams inched

closer to reality with the passage of the Elwha River Ecosystem

and Fisheries Restoration Act. All that

remained was the “small matter” of securing the funding for the project, but by

September 2011 the project was underway as an excavator set to work and began

to break up the concrete and dismantle the dam that Thomas Aldwell had worked

so hard to build. But this dam’s time had passed, and the environmental costs

associated with its continued operation greatly exceeded the small amount of

power it produced. At the official ceremony to mark the occasion, Bureau of

Reclamation Commissioner Mike Conner remarked, “Dam removal is not the best option everywhere but it is the best

option here. and it's the best option in a lot of places because the process

that we are going through these days is we are reassessing the costs and

benefits of certain facilities that exist today… I think this is not only a

historic moment here but it's going to lead to historic moments elsewhere

across the country.”

Today

the Elwha Dam is gone and the river explodes through an impressive rapid in the

heart of the canyon where the dam once blocked its flow. Only 50’ of the 210’

Glines Canyon Dam remains as work continues to completely remove it. Already

salmon have been finding their way upstream of the Elwha Dam site and the river

offers ample opportunities for exploration where one can witness first-hand

what it means to restore a river.

Destinations for a Day Exploring the Elwha

River Mouth

The river mouth is quickly transforming as

the cobble beach transitions to sand as predicted. To explore the new beach

environment head approximately 5 miles west of Port Angeles to Highway 101 mile 242.5 and

take Highway 112 west. Continue on this road for 2.1 miles (crossing the river)

to Place Road. Turn right (north) and follow this road 1.9 miles to the T

junction and then turn right (east) on to Elwha Dike Road and continue 0.1 mile

to the Elwha Dike access point. Day-use parking is available along the road.

Hike a couple hundred yards along the trail towards the ocean.

Elwha Canyon

To see the site of the Elwha Dam site, head

approximately 5 miles west of Port Angeles to Highway 101 mile 242.5 and take Highway 112 west

0.7 mile to the Elwha River. Just before crossing the Elwha bridge turn left

(south) on Lower Dam Road which is

also the turn for Elwha Dam RV Park. The parking area for the trail is to your

immediate left. The first 200 yard section of trail, constructed by Clallam

County, is wheelchair accessible and leads to a partial overlook of the former dam

site. As you approach this first overlook you will see the start of a 1/4 mile

footpath to your left. This trail was built by a Washington Conservation Corps

crew and leads to an overlook that provides the best view of Elwha Canyon and

site of the former dam.

Former Aldwell Reservoir

The former reservoir is a

fascinating landscape of gravels and sand held back by the dam, old stumps with

their springboard notches standing as reminders of the day the riparian forest

was cleared prior to flooding the reservoir, impressive views back up the

valley to the Gates of the Elwha proposed wilderness, a river that is carving

its way through a century of sediment, and evidence of vegetation that is

slowly reclaiming the corridor along the river. To see all this head about 8

miles west of Port Angeles to Highway 101 mile 239.4 just after crossing the

Elwha River bridge. Turn right (north) onto Lake

Aldwell Road towards Olympic Raft and Kayak. Continue on the road 0.2 mile to

the end and the old boat launch that was on the reservoir. From here you can

hike out onto the old reservoir and spend several hours exploring or just a few

minutes.

Former Mills Reservoir and Geyser Valley

While Glines Canyon Dam is still an active

construction site, you can drive up to explore the upper reaches of the former

Mills Reservoir and the backcountry upstream. Head about 8 miles west of Port Angeles to Highway 101 mile 239.5 and turn left (south) onto Olympic Hotsprings Road through

the National Park entrance. Continue 4.0 miles up this road and take the

left-hand turn up to Whiskey Bend. As you proceed up this road you will pass

the Glines Canyon Dam site at mile 1.2, described by members of the 1889 Press

Expedition in colorful prose as an area “rather unsafe for any nervous youths

to travel.” Continuing up the road to mile 4.0, there is a trail that leads

down to the exit from Rica Canyon and the historic start of the Mills Reservoir

(marked with a small sign that reads, "to Lake Mills"). Although the

0.4 mile trail is steep it provides an opportunity to explore the upper end of

the former reservoir and the exit of Rica Canyon. The road ends another 0.4 mile past this trail at the Whiskey

Bend Trailhead. From here it is a 1.2 mile hike to the junction of the Rica

Canyon trail which heads 0.5 miles down to the river and the downstream end of

the Geyser Valley. In contrast to the reaches downstream that are struggling to

digest 34 million cubic yards of sediment, the Geyser Valley is a great place

to see what a floodplain forest would normally look like. It provides an

interesting contrast and a potential future view of what a restored Elwha

forest could look like along the lower reaches someday.

More Photos of the Elwha

Videos:

Altair to the Sea: Kayking Down the Elwha

Going Home: The Salmon Return

Fire in the Hole: Blasting a Dam

More Photos of the Elwha

Videos:

Altair to the Sea: Kayking Down the Elwha

Going Home: The Salmon Return

Fire in the Hole: Blasting a Dam

Labels: conservation, washington